Found in Translation

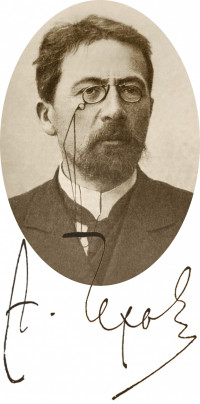

Professors Štĕpán Šimek and Rebecca Lingafelter introduce fresh translations that bring Chekhov into the 21st century.

by Ben Waterhouse BA ’06

Credit: Robert Reynolds

PROLOGUE

At first glance, it could be a scene from a Chekhov play: a few characters engaged in thoughtful conversation while seated in a spare living room among mismatched furniture. But instead, it is part of a four-day symposium, held at Lewis & Clark, devoted to the 19th-century Russian dramatist.

On this particular July day, in the black box theatre, several renowned artists and scholars have gathered to discuss the challenges of translating Chekhov into English. At the center of the action, literally and figuratively, is Štĕpán Šimek, professor of theatre. A tall man with a graying beard, Šimek wears a blue blazer over a black T-shirt bearing the word “Anton,” along with a fedora, somewhat askew, and a roguish grin.

Šimek is grinning because this panel—along with the symposium’s other lectures and performances—is a celebration of four years of intense work. Since 2014, with the help of collaborators from Lewis & Clark and within Portland’s vibrant theatre community, Šimek has created new translations of Chekhov’s four major dramas: The Three Sisters, Uncle Vanya, The Seagull, and The Cherry Orchard.

As Šimek often says, it is “an audacious undertaking,” especially for someone who has had to dust off his Russian and write in his non-native English. It is also just the latest episode of Šimek’s long relationship with Chekhov’s work—a story that begins much earlier, a continent away from Russia.

ACT ONE: Discovery

As he tells it, Šimek first came to love the plays of Anton Chekhov not in his native Czechoslovakia but in the United States while an undergraduate at San Francisco State University. He was writing an application essay for graduate school when he realized that Chekhov’s plays reminded him of his childhood. Even though he was raised under the shadow of Communist rule, Šimek moved in a large circle of family members and friends who cultivated a rich intellectual environment. “I lived on an island of seeming normalcy in a sea of oppression and grayness, nastiness and fear,” he says.

Šimek came to see Chekhov’s characters as “glued to the floor of their existence and desperate to unglue themselves.” Their neurotic banter called to mind gatherings at his family’s mountain house: “endless evenings and days talking and philosophizing, playing cards and smoking, drinking coffee and discussing things.”

As he read more Chekhov, Šimek realized the author’s stories were universal. “It’s amazing how Chekhov’s four major plays have managed to address just about every issue that people struggle with in very simple, direct, seemingly mundane ways,” he says. In his career as a director and teacher, Šimek has tried to spread this gospel. Among other efforts, in 2004 he directed Chekhov!, an ornate adaptation of some of the writer’s one-act farces and short stories that featured fur coats, fake beards, firearms, and an enormous pot of mustard. But Šimek was frustrated by people’s distaste for Chekhov’s vaunted dramas.

“I have always struggled a great deal in terms of explaining to people what it is about Chekhov that I love so much,” he says. “I believe that Chekhov, along with Shakespeare, is the greatest chronicler of the human condition—ever.”

Credit: Owen Carey

ACT TWO: Collaboration

In addition to teaching acting and movement at Lewis & Clark, Associate Professor of Theatre Rebecca Lingafelter is a prolific performer and director with a lengthy resume of productions in Portland, in New York, and overseas. On stage, she brings constant emotional directness and careful movement to her characters; as a director, she gravitates toward inventive exploration.

In 2011, she cofounded the Portland Experimental Theatre Ensemble (affectionately called PETE) with three other local performers: Amber Whitehall and Jacob Coleman, both of whom had previously worked with Šimek, and Cristi Miles. The ensemble creates unorthodox productions, often devised by performers in iterative workshops. Šimek attended their first performances—R3, a reimagining of Shakespeare’s Richard III from a female perspective, and Song of the Dodo, an examination of extinction and grief—and saw an opportunity.

“There were three women in the company, and he said, ‘We should do Three Sisters,’” Lingafelter says. “I don’t know that it was much more thought out than that.”

The PETE ensemble started workshopping the play using different translations, but Šimek, who was directing, didn’t like any of them. “I realized that maybe the problem in not understanding Chekhov lies in the translations,” he says. “The whole Anglo-American idea of Chekhov is that he’s a playwright of ennui. It’s all very boring, and everybody is sort of moaning and groaning. People think it’s all about the Russian soul. That viewpoint is all wrong.”

Šimek studied Russian for 12 years as a student in Czechoslovakia, so he decided to turn to recordings of the plays in their original language. “What struck me was how fast the dialogue is—when performed in Russian, the language is energetic, almost aggressive,” he says. He tried translating the first act of The Three Sisters and ran it by the PETE ensemble. They agreed to collaborate on the text, with the actors’ character work influencing the direction of the translation and vice versa. Lingafelter played Olga, the eldest of the three sisters.

The production, when it eventually premiered in 2014, was a major undertaking with a large cast (“a bunch of other local actors we liked,” Lingafelter says). The play’s set design placed audience members in the middle of the action, seated in the drawing room of the country house the titular Prozorova sisters long to leave.

It was a hit. One reviewer called it “audacious and original,” another described it as “iconoclastic” and “visceral.” Audiences agreed. “People were basically saying that this was the first time that Chekhov had been revealed to them.” Šimek says. “They finally understood what he was all about.”

The production was also noteworthy for the extent to which it involved the Lewis & Clark community. In addition to Šimek and Lingafelter, Charlotte Markle BA ’15 worked as dramaturg, Kushi Beauchamp BA ’16 and Mac Kimmerle BA ’16 as production assistants, and Jake Simonds BA ’14 and Jahnavi Alyssa BA ’12 as performers.

Alyssa, who had completed a mentorship program with Portland’s Third Rail Repertory Theatre, played Natasha, a young housewife who disrupts the Prozorova family’s calm. “It was terrifying,” she says. “Most of my teachers were cast members. I felt like I was working with the best.”

Credit: Owen Carey

ACT THREE: Expansion

Given the success of The Three Sisters, Šimek and the PETE ensemble were eager to continue exploring the potential of their collaborative translation process. “We felt like we hadn’t fully run the experiment,” Lingafelter says. In 2016, the company secured a $77,000 grant from the Oregon Community Foundation’s Creative Heights initiative—a program intended to enable artists to test new ideas—to create new translations of Chekhov’s remaining major plays and mount a full production of one of them.

Over the next two years, Šimek and PETE worked with actors, directors, and dramaturgs to develop the new translations. Šimek presented texts to performers, who would workshop the characters and suggest changes for incorporation into future drafts.

Cristi Miles, who directed PETE’s 2018 staging of Uncle Vanya, says, “Having the actor’s voice in the translation process was so empowering. It really gave them a sense of the character.”

Lewis & Clark has a really strong footing in the Portland theatre community. We have alumni who are critics, who are actors, who are designers.” Rebecca LingafelterAssociate Professor of Theatre

Šimek describes his translations as having a directorial point of view. He tries to bring out the elements of Chekhov’s structure and rhythm that support his idea of what the plays mean, but he pays little concern to literal meaning or historical accuracy. The translations are peppered with contemporary language and 20th-century pop culture references, which make the characters more approachable but also emphasize the distance of their experiences.

“My translations are neurotic,” Šimek says. “They are all over the place. They are inconsistent. I don’t care about consistency. I care about the truth.”

PETE continued to work with Lewis & Clark students and alumni through staged readings of The Seagull (Sam Reiter BA ’16 and Rosie Lambert BA ’17) and The Cherry Orchard (Eliza Frakes BA ’19 and Kushi Beauchamp BA ’16) as well as the full production of Uncle Vanya, with Delaney Bloomquist BA ’18 as dramaturg and Lambert, Trevor Sargent BA ’16, and Molly Gardner BA ’12 as members of the production team.

“Lewis & Clark has a really strong footing in the Portland theatre community,” Lingafelter says. “We have alumni who are critics, who are actors, who are designers. The production teams for nearly all of my PETE shows are L&C alumni.”

PETE completed the goals of its grant with a well-received, cabaret-like production of Uncle Vanya, but Šimek and Lingafelter, in the spirit of their department’s mission of educating artist- scholars, wanted to connect the project to the academic community. So they conceived a symposium to bring artists and scholars together to discuss the contemporary meaning of Chekhov and present a marathon reading all four of the new translations— a “Chekh-O-Rama”—to the public.

ACT FOUR: Celebration

On the third day of the Chekhov symposium, groups of performers gathered outdoors between panel discussions to run their lines for the next day’s readings. Chekhovian cries—“Masha! Masha!”—rang through the air above the trees by the reflecting pool.

Credit: Owen CareyAt Fir Acres Theatre—which opened, as it happens, with a production of The Cherry Orchard in 1977—directors, dramaturgs, scholars, critics, and enthusiasts mingled around a participatory sculpture: an abstracted cherry tree trimmed with instruments and Czechvar beer bottles. Mia Convery BA ’19 kept the show running.

“I’m so grateful that Lewis & Clark’s theatre department trusted me to work on the symposium,” Convery says. “I loved being able to work with professional theatre artists and have so much responsibility on a high-impact event. It was stressful, but knowing that I could do it after we finished felt amazing.”

Jahnavi Alyssa BA ’12, who now works as a performer in Salt Lake City, returned to Portland to reprise her role in The Three Sisters in the Chekh-O-Rama. “Everyone involved was so kind and so considerate,” she says. “I could feel how much I had grown up as a person and as an actor.”

With the symposium now complete, Šimek continues to pursue his translation work. He is collaborating with Jerry Harp, associate professor of English, to edit the texts in preparation for publication in an anthology and, Šimek hopes, in performance editions with industry leader Samuel French. “I really do want them to be produced,” he says.

Šimek’s translations have already found life beyond Portland. The Seagull was produced by Roosevelt University’s Theatre Conservatory in Chicago and The Three Sisters at Bowdoin College in Maine. A Seattle company is considering Šimek’s Uncle Vanya for an upcoming production.

The texts are also being used at other colleges. Yuri Corrigan, who teaches Russian and comparative literature at Boston University, uses excerpts from Šimek’s translations to augment more literal, scholarly versions. “I love that Štĕpán doesn’t worry about historical accuracy or internal consistency in his plays, and is wholeheartedly devoted to figuring out what will work on stage in the moment of performance,” he says. “This has been a revelation for me, as someone who has spent years studying these works more as texts than as plays.”

For Šimek, revelations like Corrigan’s are the purpose of the translation project. “Every generation needs a new translation that keeps the work relevant and accessible,” he says. “I’m on a mission to reintroduce Chekhov to American audiences.”

Ben Waterhouse BA ’06 is a journalist and editor in Portland. His writing about theatre can be found in The Oregonian.

Translating for Today

Šimek is currently collaborating with Jerry Harp, associate professor of English, to edit his translations in preparation for publication in an anthology. In the meantime, his texts are being used at other colleges. Yuri Corrigan, who teaches Russian and comparative literature at Boston University, uses excerpts from Šimek’s translations to augment more literal, scholarly versions. “I love that Štĕpán doesn’t worry about historical accuracy or internal consistency in his plays, and is wholeheartedly devoted to figuring out what will work on stage in the moment of performance.”

Šimek’s unique style is evident in these excerpts from his translation of The Three Sisters and Julius West’s more traditional 1916 version.

West

A knowledge of three languages is an unnecessary luxury in this town. It isn’t even a luxury but a sort of useless extra, like a sixth finger. We know a lot too much.

Šimek

To know three languages in this shithole is an unnecessary luxury. It’s not even a luxury; it’s more like some sort of unnecessary add-on, like having a sixth finger. We know lots of pointless garbage.

West

Let’s all get drunk and make life purple for once!

Šimek

Let me have a glass of wine! What the hell, life’s like a raspberry, enjoy it before it rots!

West

Well? After our time people will fly about in balloons, the cut of one’s coat will change, perhaps they’ll discover a sixth sense and develop it, but life will remain the same, laborious, mysterious, and happy. And in a thousand years’ time, people will still be sighing: “Life is hard!”—and at the same time they’ll be just as afraid of death, and unwilling to meet it, as we are.

Šimek

Let’s see. After we’re gone, people will fly around in hot air balloons, wear different suits, maybe even discover a sixth sense and develop it, but life will stay the same: hard, full of mystery and happiness. Even in a thousand years from now, people will moan and groan: “Oh, life’s so hard!” – and all the while, just like now, they’ll be scared and they won’t want to die.

West

MASHA. It seems to me that a man must have faith, or must search for a faith, or his life will be empty, empty… . Either you must know why you live, or everything is trivial, not worth a straw.

Šimek

I think that one has to believe in something, or at least look for something to believe in, otherwise life is empty, empty… . Either one has to know why one’s alive, or everything would be nonsense and nobody would even care.

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219