L&C President Invited to State of the Union

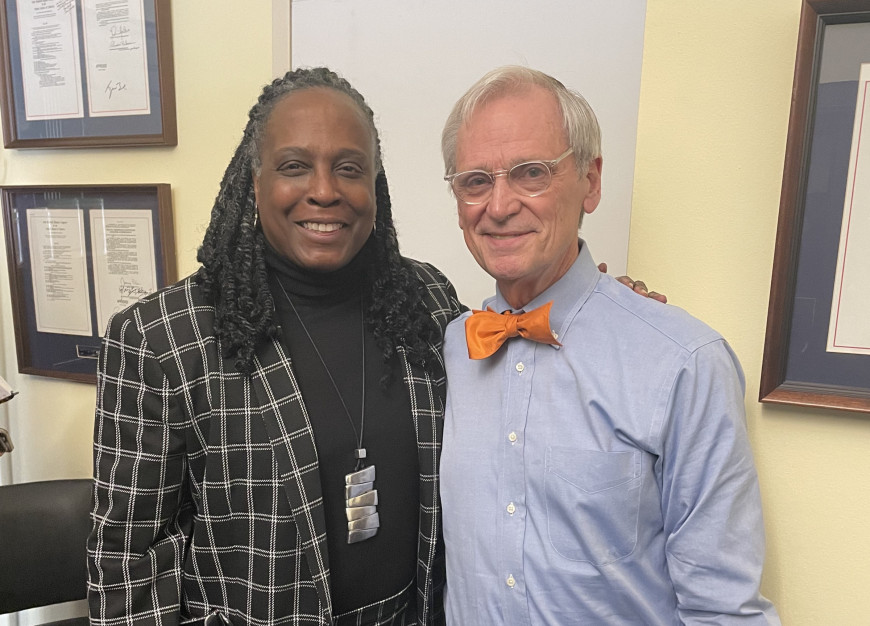

Dr. Robin Holmes-Sullivan attended the State of the Union address in Washington, D.C., on February 7. She was the special guest of Oregon Congressman Earl Blumenauer BA ’70, JD ’76.

Open gallery

Did you watch the televised State of the Union address on February 7? If so, you might have caught a glimpse of a familiar face–Lewis & Clark’s own president, Dr. Robin Holmes-Sullivan.

Holmes-Sullivan was invited to attend the ceremony as the guest of Oregon Congressman Earl Blumenauer BA ’70, JD ’76, D-OR. As Blumenauer’s guest, Holmes-Sullivan had a reserved seat in the gallery of the House of Representatives, along with other guests of members of Congress. Each member is allowed one guest.

“I was honored and humbled to be able to represent Lewis & Clark at this important annual ceremony in our nation’s capital.”

Dr. Robin Holmes-Sullivan

President Holmes-Sullivan also attended a special reception hosted by House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, D-NY, and another hosted by the Library of Congress, prior to the start of the State of the Union address.

“I was honored and humbled to be able to represent Lewis & Clark at this important annual ceremony in our nation’s capital,” Holmes-Sullivan said. “Congressman Blumenauer has been a tremendous friend to the college over the years, and this is yet another example of that friendship. I cannot thank him enough.”

Blumenauer graduated from Lewis & Clark in 1970 with a bachelor’s degree in political science. He received his juris doctor degree from Lewis & Clark Law School in 1976.

President Holmes-Sullivan at the State of the Union

History of the State of the Union

The annual State of the Union address, during which the U.S. president updates Congress and the American people on the country’s condition and proposes various policy initiatives, is based on a requirement in the U.S. Constitution that the president “from time to time give the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.”

President George Washington delivered the first State of the Union (then called an “Annual Message”) to a joint session of Congress in person in 1790. President John Adams also delivered his annual report in person, but President Thomas Jefferson sent a written message to Congress, starting a tradition that would last for more than 100 years. President Woodrow Wilson delivered his speech in person in 1913, reinstating the practice of speeches delivered in person. The term “State of the Union” as a way of referring to the annual addresses was introduced in 1947 under President Harry Truman.

Little Known Facts About the State of the Union

-

Shortest State of the Union:

The award goes to President George Washington, whose 1790 State of the Union message was reportedly slightly over 1,000 words. -

Longest State of the Union:

President Jimmy Carter’s address was the longest, at a reported 33,667 words. Fortunately for members of Congress, he delivered that message in writing, not in person. President Bill Clinton is said to have given the longest in-person State of the Union speech in 2000, taking a total of 1 hour, 28 minutes, and 49 seconds to deliver it. By comparison, President Joe Biden spoke for 1 hour, 5 minutes and 8 seconds in his State of the Union speech last year. -

Has every president delivered an annual message to Congress?

No. Neither President William Henry Harrison nor President James Garfield delivered State of the Union messages. Both men died early in their presidencies before they could do so. -

Have any State of the Union speeches had long-term impacts?

Yes. The Monroe Doctrine was announced by President James Monroe during his State of the Union address in 1823. James Polk is credited with significantly increasing westward migration as a result of his 1848 speech. In 1941, FDR delivered his famous “Four Freedoms” speech as part of an effort to move the country beyond isolationism. Lyndon Johnson launched his war on poverty in his 1964 message. George W. Bush’s reference in his 2002 State of the Union to the “Axis of Evil” became an oft-repeated refrain and helped solidify support for military intervention in the Middle East. -

Does the president decide where and when to deliver the State of the Union?

No. If the address is being delivered in person, it is up to the Speaker of the House to issue an invitation to the president to come to the House of Representatives to deliver the speech. -

Why is the speech delivered in the House of Representatives instead of the Senate?

Because the House chambers are much larger than the Senate chambers. There would be no way to comfortably accommodate all of the representatives, senators, members of the president’s cabinet, and guests in the Senate chambers. -

Are all the members of the president’s cabinet required to attend the State of the Union?

No. Just as depicted in the television show “Designated Survivor,” one member of the cabinet is sequestered with Secret Service agents at an undisclosed location in order to ensure there is someone to step in as president if everyone in the line of succession is killed during the ceremony. Since the 9/11 attacks, Congress has adopted a similar practice, assigning a few members of each house to go to undisclosed locations away from the Capitol. -

Do Members of Congress compete to get the best seats for the ceremony?

Yes. Some members grab seats first thing in the morning, just to make sure they get an aisle seat for the evening ceremony. Sitting on the aisle means they have a good chance of shaking the president’s hand and being seen on TV. -

What special tradition got its start at the 1982 State of the Union address?

The practice of presidents inviting and honoring special guests got its start in 1982, when President Ronald Reagan praised Lenny Skutnik for jumping into the frozen Potomac River to save a passenger from a downed plane. Special guests invited and honored by presidents during the ceremony are now often referred to as “Lenny Skutniks.”

Sources include the Congressional Research Service, the Council on Foreign Relations, and the Washington Post.

More Newsroom Stories

Public Relations is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email public@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

Public Relations

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219