Environmental, Natural Resources, & Energy Law Blog

Meaningful Pathways - Alicia Kooda

Meaningful Pathways

Alicia Kooda

November 2023

The issue of meaningful pathways for local transit options is environmentally focused. Access and use of pathways affects people’s physical and mental health. Pathways are critical to the community and have major impacts on commerce. A lack of local transit options for safe alternative travel is a solvable problem that could improve our lives and our world. The solution in America is streamlined policy and funding. In addition, communities should embrace walkability, safe bike lanes, removal of extraneous car lanes, traffic light and pedestrian lights conducive to pathways, and monorail or other local light rail options. Meaningful is placed in front of pathways because the safety and effectiveness of any local transit system will depend upon engaging people in the use of the pathways. Considerations for work, food, enjoyment, safety, and convenience must be a part of each community’s approach.

The following are some of the existing challenges with the typical approach to the issue of interconnected alternative local transit options. The predominant amount of existing bike lanes are dangerous. 1 Any proximity to vehicles carries too much risk for meaningful use with assured safety. Bike pathways are only useful certain times of the year due to weather limitations. Walkways, cross walks, bike paths, and other similar options are typically afterthoughts not connected due to funding via each commercial developer with some local government or grant funding actions. Local transit is not meaningful if it stops in five places without connecting grocery stores, homes, and work.

Conceptually and practically, American policy makers and federal agencies are arguably well positioned and experienced at construction and solving major issues impacting citizens. Major US federal government initiatives appropriate vast sums of money to important issues like defense (over $200B), and renewable energy loans through the Department of Energy (over $40B). 2 A bike path that connects major stops within a community of an average size of 100,000 citizens would range in cost. Based on my experience in city and federal construction projects an estimate is approximately $5M for that size community. An example of the cost for local transportation rail is Salt Lake City. The Utah hub is expanding to add additional lines. The Transit 2030 estimate for rail, bus, and streetcars expansion is $3.8B. 3

The reality of current attempts to improve local transit is wrought with barriers and challenges. Federal to regional then local funding for transit includes too many obstacles. For example, the CAPCOG that has worked on commuter rail in the Austin, TX area for over 20 years had no movement beyond land acquisition from Union Pacific rail for a majority of the time. Elected representatives typically sit with government personnel on planning meetings at the regional level and compete against one another in regional battles for limited grant and government funds. A more decisive roll out from the top on project execution would prevent a lowest priced technically acceptable “race to the bottom”. This also impacts jobs and industry in these areas. Typically, private partners are left behind in the government planning process.

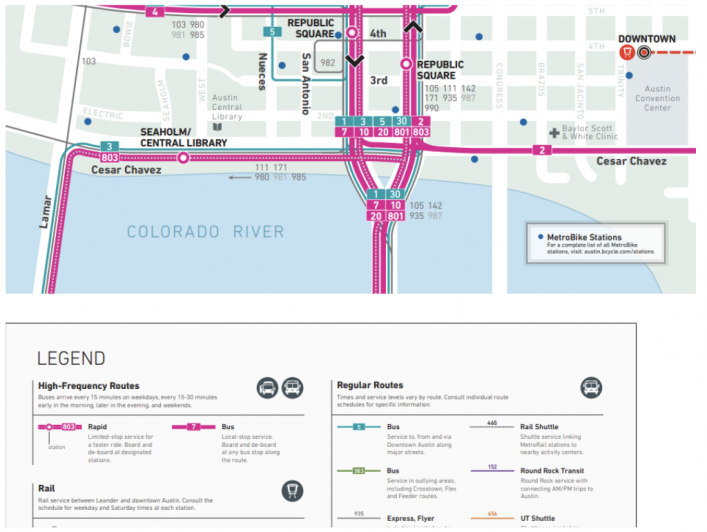

Funds end up going to marketing and information campaigns rather than improving transit. Austin’s transit map is an example of this type of redirecting focus. The bus lines are the same color as the rail lines. 4 The Rapid Routes blue line that looks like a rail map but it is a bus route. To me, this is an example of trying to look like you provide meaningful transit rather than making big decisions to update a city plan to reduce reliance on fossil fuels. Austin’s I-35 corridor is only one example but it is egregious that the plan doesn’t address the main highway commute. Within the city, a five-mile stretch can take over an hour. The resulting fumes recurring daily is just one instance of what a huge impact meaningful pathways can make.

Forward Thinking.

What’s next? How do we create meaningful pathways? What barriers exist in funding mechanisms and public participation? How should the law deal with this issue? One part of the solution will be Federal and state laws mandating infrastructure changes and associated funding. Another key part is incentives for commercial entities to contribute to updates in development through tax credits. These policies will require agency positions and funding tied to completion and sustainment of these infrastructure projects. To implement this successfully, Federal, state, and local funding mechanisms need to shift priorities. Additionally, local zoning and development policies are necessary that incorporate meaningful pathways into planning and development.

In creating new law as described above to implement updates to create meaningful pathways and local transit, local community involvement is critical. In order to make changes to existing laws that govern planning and zoning, elected officials will need to respond to an informed and engaged community. Most localities will have to make tough choices regarding either removing roads or homes to make space for safe meaningful local transit options. To be invested at this level, the money and benefits for each community should have direct impact and be clearly communicated. Private engagement will help move this rather than attempts at volunteering or steering committees and other previous methods from single focused interest groups like local parks boards or nonprofits. The reality is these changes could be financially beneficial for local businesses and owners of industry in each community. They will be motivated to make it happen. This will require a lot of community partnerships and education. The work requires impacts to laws dealing with moving federal, state, and local funding. Too many restrictions prevent meaningful engagement with industry in using federal funds.

As noted, there are challenges to achieving the goal of meaningful pathways to include gaining local support and connecting across multiple cities. Public opinion and political will power as attachment to status quo and car use is lifelong. Facing these challenges means engaging businesses as route stops and partners to help with local politics. Broad new steps in policy and funding lines. The enactment needs state level support and legislation to address crossing municipalities. An example of the execution for this idea is the northern Utah communities. The largest employer is Hill Air Force base. If transit connects to the base, the Air Force should match with transit within the base. Stops at businesses like Harmons, Walmart, local shopping areas and hotels as well as a connection to the Salt Lake City transit, will help facilitate the support for building and use of improved transit.

There is a chicken or the egg piece to this issue. Correct infrastructure changes and the right approach to pathways ensures the use and success of systems. An example of the detracting argument against alternative transit are existing systems that are underutilized and perceived as “trashy” or unsafe. Salt Lake City trams and Las Vegas monorails already connect the major parts of both cities. Why do people not use these transit options? COVID and safety concerns are one example of potential concerns, in addition to a restriction of flexibility as well as the incorporation of walking as transit can only reach large cell stops. However, I also suspect that if people didn’t have the option to drive they would “jump on board” local transit. A good example in Salt Lake City, UT and Austin, TX, is college football game days. When traffic to the stadium overwhelms the streets, people of all ages and body types adapt to using various types of transportation (bikes, walking, and train).

Any meaningful pathways initiative needs to incorporate road lane removal. Less options for driving will motivate users to alternative transportation options. The more people biking, walking, and using trains, the safer those options become. I was recently in “Old Town” Alexandria, Virginia. The walkable policies there included a prohibition on cars turning on red lights to improve pedestrian safety, dedicated walking streets with no vehicles, and zoning policies. The folks were out on the walkable streets engaging in a debate about zoning policy. The concept of in-fill was at issue. One side wants restrictions and less flexibility, while the other supports development. Development is a tricky term because it is one of those words that carries negative and positive connotations. In this case, one side is saying “not in my back yard” and the other side is saying “yes in my back yard”. Responsible development includes people of multi-tier economic status because a community functions by multi-tier economic status inputs. Jobs, garbage, street upkeep, transit, food, and businesses require many economic statuses in order to function. If people cannot get to the restaurant to wash dishes then the dishes are dirty.

Success Stories.

An article included in the footnotes here explains how Los Angeles and Phoenix are on the way to becoming walkable and the tactics they engaged. 5 If you’ve seen both cities back in the early 1990s or before, you know why the article title denotes this as “surprising”. Phoenix’s 2050 plan was a bipartisan effort approved by voters with special interest from the mayor who personally was affected by a lack of transit options. 6 This article is a good introduction to Los Angeles’ zoning based changes to improve walkability. 7 Any city looking to improve meaningful pathways will need to update zoning. I included these examples because it shows how it is “never too late” to makes the changes towards meaningful pathways.

Stakeholders.

I know from my experience with my parents and grandparents that eventually the ability to drive goes bit by bit. Night driving goes first then the rest or it happens all at once. From medical appointments, to groceries, church, and social opportunities, retirees and the elderly can benefit from alternative transportation cities. Just recently, I personally started a list of places to consider for my own “golden years”. Salt Lake City, Port Angeles, Helena or somewhere similar are making the list due to walkability, local businesses, community engagement and transit options. I want to live close to nature and necessities and I do not want to drive. I’m not alone. Respect care givers is one of many websites marketing to the older user group regarding places to live based on walkability. 8 The most notable thing, to me, from the list is they are all large metropolitan areas. I believe economic development directors of mid-sized to small communities have a real commercial opportunity in revamping their towns to be walkable and incorporate local transit. Retirees can literally move anywhere and I bet most people would prefer a smaller community to the big city, if it offered meaningful pathways and met their essential needs.

Unfortunately, outside the success stories above that had the luxury to incorporate pathways at the start or large city centers with budgets to overhaul neighborhoods, most places add bike lanes or multi-use paths through city development codes that require developers to put them in as a part of housing projects. This creates piecemeal attempts that may or may not connect, be similar sizes, and most critically the maintenance plans are typically non-existent. The public involvement and dedication in these projects is admirable. I served as a parks board advisor for the City of Elgin, TX. The interested citizens helped city officials write applications to win grant money to get ADA ramps and sidewalks, as well as a Texas Parks and Wildlife grant for a trail. The engagement is great but the struggle for a few dollars that can only create a few miles of pathways is frustrating. Instead of placing all the responsibility on a few, the federal and state government should place this priority where it belongs –at the top in terms of legislation, funding and execution.

Involving businesses in the local area’s plans, engaging and educating the community, along with changes to laws and lines of federal funding, are major steps towards addressing the issue of creating meaningful pathways. The improvements to our life in health benefits, environmental impacts, local economic development stimulation, and community engagement with positive mental health gains are critical to our future. The cost is not the biggest challenge. As noted, dependence and acceptance of a car-centric society has kept the status quo despite the safety issues, physical, mental and community detriments. If economic gains and profits literally drive our car culture, I think the same motivators can build meaningful pathways. Government and local businesses can engage in the industry of changing the way we transit. In the process, new opportunities will emerge for economic growth. Ultimately, we just need some policies and money to flow in a new direction.

Continue to the next pages for supporting images, transit maps and links to additional information.

Supporting Images

The following pictures bring home the concept of a meaningful pathway better than words.

Bike lanes that are dedicated, safe, green, and removed from motor vehicle danger.

Photo source: Separated Bicycle Lanes Coming to McClellan Road – Update | Walk-Bike Cupertino (walkbikecupertino.org)

Photo source: Saitama City Plans 200km of Bicycle Lanes Over 10 Years (tokyobybike.com)

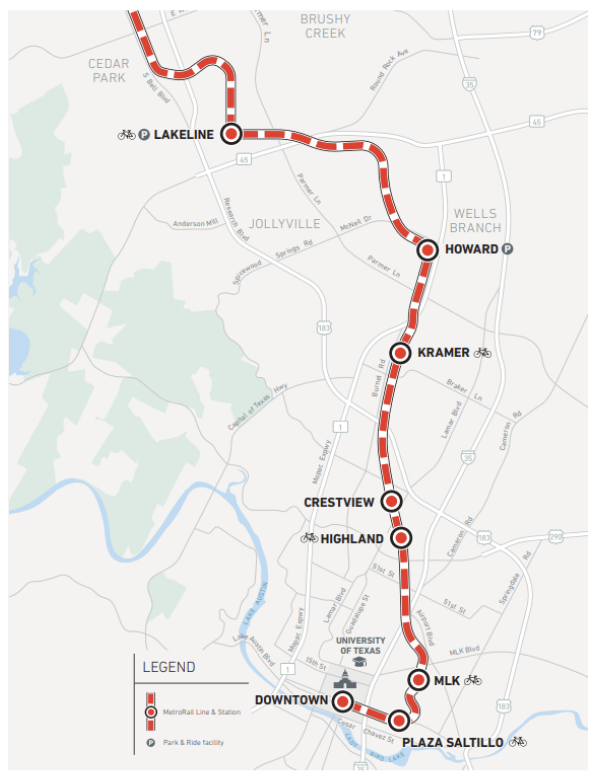

Rail that connects neighborhoods to grocery stores and downtown businesses.

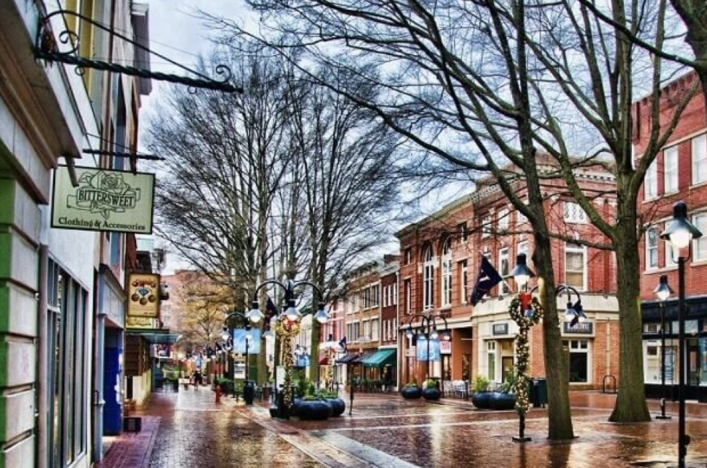

A photo of a walkable downtown.

Photo source: Why do walkable cities matter? - UrbanizeHub

Transit maps appearing connected. The reality is there are issues with timing and locations.

Resources

- Bicycle Safety | Transportation Safety | Injury Center | CDC

- BUDGET-2021-BUD-9.pdf (govinfo.gov)

- Sustainable Transportation Case Study: Salt Lake City, Utah (dot.gov)

- The Surprising U.S. Cities That Are On Their Way To Becoming Walkable (fastcompany.com).

- Phoenix Mayor’s 35-Year Public Transit Expansion Plan Aims to Make the City Less Car-Dependent (businessinsider.com).

- Re-Zoning Los Angeles: Can we legalize a walkable City? - Los Angeles Walks.

- 23 Best Walkable Cities to Retire In - RespectCareGivers

- Separated Bicycle Lanes Coming to McClellan Road – Update | Walk-Bike Cupertino (walkbikecupertino.org)

- Saitama City Plans 200km of Bicycle Lanes Over 10 Years (tokyobybike.com)

- Notes on the APTA conference in Salt Lake City - Trains Magazine - Trains News Wire, Railroad News, Railroad Industry News, Web Cams, and Forms

- Why do walkable cities matter? - UrbanizeHub

Footnotes

1 Approximately 130,000 people are injured in bicycle/motor vehicle incidents in the US per year. Bicycle Safety | Transportation Safety | Injury Center | CDC

2 US Department of Defense Budget 2023 $704B. BUDGET-2021-BUD-9.pdf (govinfo.gov)

3 Sustainable Transportation Case Study: Salt Lake City, Utah (dot.gov)

4 See maps located towards the end of the blog.

5 The Surprising U.S. Cities That Are On Their Way To Becoming Walkable (fastcompany.com).

7 Re-Zoning Los Angeles: Can we legalize a walkable City? - Los Angeles Walks.

Environmental, Natural Resources, and Energy Law is located in Wood Hall on the Law Campus.

MSC: 51

email elaw@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-6649

Environmental, Natural Resources, and Energy Law

Lewis & Clark Law School

10101 S. Terwilliger Boulevard MSC 51

Portland OR 97219