Good Trouble: Building a Bigger Tent at the Crossroads of Oppression

Open gallery

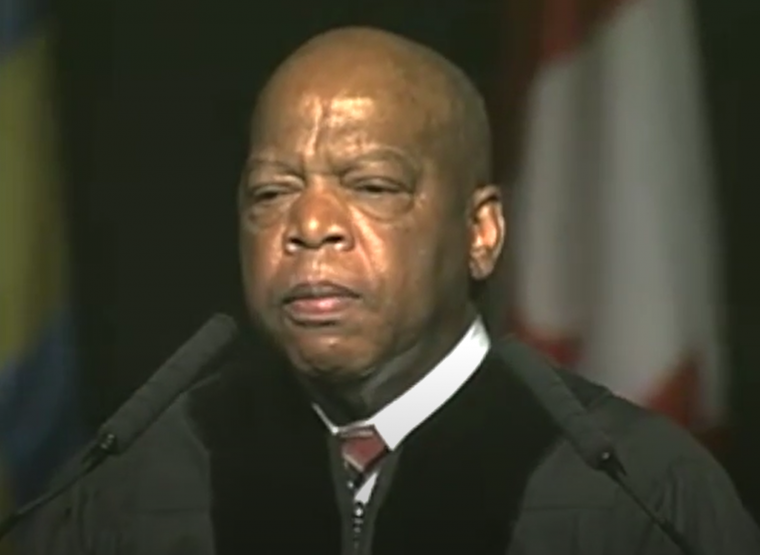

Today, we celebrate the life and legacy of the great civil rights icon, Congressman John Lewis, as he is laid to rest in Atlanta. As we reflect in honor of the historic occasion, we considered how those in the animal protection movement—for whom it’s second nature to envision nonhuman individuals when someone mentions oppression or social justice—can widen the circle of our compassion.

When Congressman Lewis gave the commencement address at Lewis & Clark Law School in 2008, he urged: “As law students… you must go out and get in trouble. You must stand up and speak out and defend the rights of all humankind. That is your mission.” We now ask how that directive applies to animal protection advocates.

In a world rife with racism, sexism, ableism, misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, and other forms of oppression, the life of kindness that we aspire to achieve can be more expansive. One way of doing this is by embracing a more holistic approach to our advocacy—because it is increasingly clear that wherever nonhuman animals are exploited, humans, especially those who are historically marginalized, are usually exploited too. And, we must regard these exploited humans as also deserving of our activism when we “stand up and speak out” for the oppressed. This has never been more evident than in recent months.

As COVID-19 has ravaged our country, it has revealed that those charged with the work of slaughtering the billions of farmed animals that we fight to protect are commonly immigrants and people of color. These are the same people who quickly became infected with COVID-19, who were then forced to return to work as “essential workers”, and without adequate regard for their safety. To date, it is estimated that more than 37,000 meatpacking workers have tested positive for COVID-19 in the U.S. and more than 170 have died, according to the Food and Environment Reporting Network. The pandemic has laid bare that the same corporations that exploit farmed animals are also exploiting people and the environment, as they grab ever more profits at the expense of those they oppress.

The crossroads of oppression were evident yet again when xenophobia fueled by the recent COVID-19 outbreak caused a surge in anti-Asian bias. Those who stigmatize one group as being the “source” of a virus outbreak are often oblivious to the role of the U.S. in creating conditions that facilitate the spread of zoonotic diseases. The first wave of the 1918 influenza pandemic, which eventually killed an estimated 50 to 100 million people worldwide, likely began on a farm in Kansas. Scientists—including most recently in the U.N. Environment Programme Report, Preventing The Next Pandemic: Zoonotic Diseases and How To Break the Chain of Transmission—have raised the alarm that factory farming is creating dangerous conditions that could fuel the next pandemic.

A further example of oppression that animal protection advocates should address when we talk about social justice is the inequity of access to fresh fruits and vegetables. Those fortunate enough to live in an area with a decent grocery store or, better yet, a farmer’s market, may not recognize it as a privilege frequently denied to many lower-income communities and communities of color. This economic inequality is yet another form of oppression—one that is sometimes overlooked in discussions urging a plant-based lifestyle. And, of course, few of us would have plant-based foods were it not for the farm workers who plant, grow, and harvest the produce we eat. We cannot talk about social justice and a plant-based lifestyle while also ignoring the remarkable labor of these farm workers—2.4 million across the country—the vast majority of whom are new immigrants when they start, and, for over half of them, their undocumented status keeps them from receiving basic protections that so many of us take for granted.

Finally, we cannot effectively work toward justice without joining the national reckoning about long-standing structural racism, following the murder of George Floyd. Racial justice protests have inspired people around the country to re-examine how our everyday actions can be more inclusive, more compassionate, and how silence in the face of injustice can too often connote agreement. At the Center for Animal Law Studies, we are listening and learning more intently. We are also asking ourselves and our colleagues throughout the movement how we can all do more to combat structural racism, support criminal justice reform, and facilitate a more diverse and inclusive animal rights/protection movement.

So as we honor the life and legacy of John Lewis, we can and must expand our tent as animal protection advocates to address oppression, in all its forms—because oppression never exists in a vacuum. There are no easy answers. But we can start by taking the time to recognize—wherever we see the oppression of nonhuman animals—the other forms of oppression that are right before our eyes. When we start to examine how oppression affects humans and nonhumans alike, we will move toward a holistic approach to advocacy that is not only more inclusive, but also more effective.

As for John Lewis, in an interview with Krista Tippet entitled Love in Action, he described how his own circle of compassion as a child began with the flock of chickens on the family farm:

“I loved those chickens. I talked to those chickens. I preached to those chickens, and I used to cry when my mother or father wanted to kill one of those chickens for dinner. They became part of my life. And my first nonviolent protest was protesting against my parents for getting rid of those chickens.”

The child who nonviolently protested to protect the lives of the chickens to whom he preached went on to change the world by nonviolently protesting Jim Crow laws, leading to the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

As we move forward in our animal protection work, let us all ask how we can get into “good trouble” defending the rights of all the oppressed—because whether human or nonhuman, their suffering compels us to speak up and make a difference.

The Center for Animal Law Studies (CALS) was founded in 2008 with a mission to educate the next generation of animal law attorneys and advance animal protection through the law. With vision and bold risk-taking, CALS has since developed into a world-renowned animal law epicenter, with the most comprehensive animal law curriculum offered anywhere. In addition, CALS is the only program that offers an advanced legal degree in animal law and three specialty Animal Law Clinics. CALS is a nonprofit organization and is only able to provide these educational opportunities through donations and grants. To create a legacy for animal protection, please check out our Animal Law Legacy Program.

More Center for Animal Law Studies Stories

Center for Animal Law Studies is located in Wood Hall on the Law Campus.

MSC: 51

email cals@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-6960

Center for Animal Law Studies

Lewis & Clark Law School

10101 S. Terwilliger Boulevard MSC 51

Portland OR 97219